Elusive as they are (in both theory and practice), concepts like cognitive load, metacognition, interleaving and spacing all speak to a profession that’s doing its level best to keep pace with the realities of what our learners need.

The challenges

To make all this work for us, though, we’ve got to come to terms with two tensions: firstly, we’ve got to recognise the lives our young people lead: between 86% and 96% of a child’s vocabulary is also present in that of their parents’, and by the age of 3, children from lower-income households are exposed to 30 million fewer words than their more affluent peers - a word gap that continues to grow as learners do. A cursory glance at the Literacy Trust’s research into literacy and life expectancy also confirms all kinds of uncomfortable truths about the insidious impact of low literacy rates on people’s lives.

Secondly, in light of this, we must understand our own educational deliverables and acknowledge curricular and logistical realities: the recent focus on curriculum and the 3Is- intent, implementation and impact- has intensified the need for leaders and teachers to be at least confident in the rationale for what is happening in the classroom. In other words, why this? Why now? How impactful will this be for our learners? How do we know what we’re working with in terms of our pupils' individual and collective gaps?

Vocabulary instruction - and our ability to do it - isn’t only a useful barometer, but a transformative tool in our quest to join all these dots. And I found this out by accident.

My happy accident

In all honesty, after reading various blog posts, articles and books on vocabulary, I couldn’t see it: after all, why do pupils need to know that ‘compassion’ consists of a root word meaning ‘with’ (com) and ‘suffering’ (passion)? Beyond impressing the odd examiner, what real purpose could the word ‘misanthropic’ serve for my pupils?

As well as this, the awful scramble for curriculum time - even before you begin to factor in the odd school photo, vaccination or fire alarm- made the idea of bringing these words into my classroom even less attractive. However, I’ve always had what you might term a penchant for trends (there will almost certainly be colleagues and friends reading this that will at least be nodding along in agreement and probably laughing). So, when September rolled around and I introduced my new year 9s to the irresistible Ebeneezer Scrooge, describing him as ‘misanthropic,’ breaking the word into its component parts: mis meaning ‘hatred,’ and anthropic meaning ‘humans.’ Something remarkable happened: a stone was dislodged in my mind. Something shifted in my understanding of teaching.

Ebeneezer Scrooge, you see, isn’t simply someone that’s mean-spirited , unfriendly and cruel to people. There’s something more cynical and corrosive about him. It goes deeper than that. It isn’t just one person or a few individuals that Scrooge dislikes: he has a deeply rooted hostility towards humanity in its entirety.

It clicked for me: on one level, giving pupils the means to encapsulate this sharpens the precision with which they are able to discuss their views. But on another level, demystifying the etymology of a word can be a catalyst for pupils’ understanding of the word - and by extension - the character itself. And it didn’t stop there, either. As we moved through the text and beyond, we were able to use the word in multiple contexts, comparing and contrasting to other characters, and in the texts beyond. His nephew, Fred, became the anti (opposite) thesis (idea) to Scrooge: by extension, why would Dickens deliberately manufacture this scenario?

From vocabulary to concept

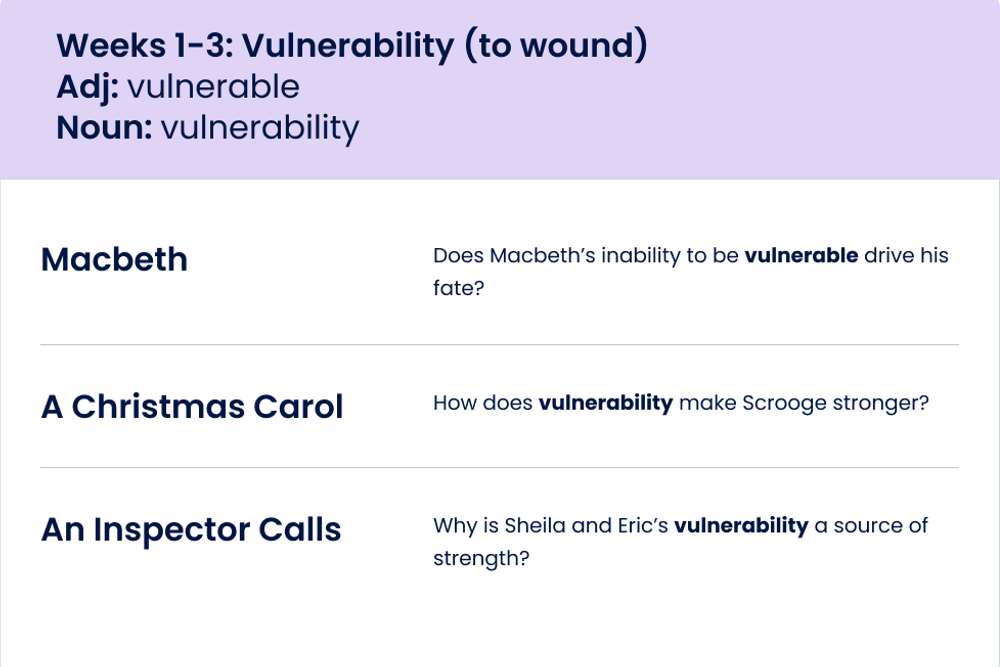

My own understanding- and the pupils’ - seemed to take on a life of its own after that. They were able to use the word in their writing as well as in class discussions. Eventually, by the time this year 9 class made it to year 11, such was the shift in my own understanding that we were able to move to an entirely concept-driven curriculum, interleaving concepts between texts: under a single concept such as vulnerability, we were able to discuss characters across A Christmas Carol, Macbeth and An Inspector Calls.

Learning is messy and not always linear, just like vocabulary. But we can harness that and use it to broaden and deepen our pupils’ knowledge.

This kind of discussion becomes even more interesting when we begin to consider the more recent focus upon disciplinary literacy, and the types of thinking we need in order to be successful across the various disciplines. When I was newly qualified, I remember carrying out an action research project as part of my induction in which I compared the performance of two classes: one had been taught key vocabulary that I’d deliberately selected that would help support their answer in an assessment, and the other class was not exposed as explicitly to them. I remember presenting on this, and the Deputy Headteacher at the time enquiring: ‘you mean you taught one class something, not the other, and that class did well?’ I wanted the ground to swallow me whole. I didn’t have an answer.

But now I do.

Yes, the vocabulary played an important role in the pupils’ performance. But it was only part of the story: something more profound had shifted for the class. To borrow an analogy from a colleague here at Bedrock, we might usefully understand the brain as our hardware, but language as representative of a learner’s software. We might have the world’s most powerful supercomputer on our shoulders, but it’s useless if we haven’t got the appropriate software to make use of its powers.

Scrooge’s misery isn’t just a dislike of others: it’s a deeply profound cynicism of humanity in general. Which begs the question: why humanity? How might Dickens have been using this character as a construct to explore something deeper and more profound about the human condition?

What this means for teaching vocabulary

What’s the upshot of all this, then? In short, if there’s any kind of silver bullet in education, it has to come back to purposeful sequencing of knowledge. Yes, vocabulary plays a part, but as educators, we need to be prepared to select and codify the most powerful, impactful knowledge that our learners need to succeed in the classroom and beyond. ‘Academic vocabulary’ can be a little elusive, as there’s not necessarily a definitive list for a given text, but that’s the beauty of it. This is where we come in: teachers can - and should - be the arbiter of knowledge, and the gateway to bridging the gap between pupils that say/think ‘this kind of language isn’t for me’ and pupils that find the assimilation of knowledge and ideas much simpler.

We need to move away from ‘vocab lists’ towards a more conceptual framework for teaching. The limitless variables of socioeconomics, prior attainment, knowledge gaps, confidence and time constraints make the idea of progress a seemingly impossible moving target to hit. Yet, if we create the space in our own minds, teams and schools to think more deeply about sequencing of concepts and powerful knowledge, then we are much more likely to coherently plan and present learning experiences to pupils that lessen their cognitive load, that heighten their confidence to engage with complex academic tasks, and that support them to find their academic voice.

A practical example

Inevitably, this looks different in each discipline. But let’s take a moment to consider how we frame units of learning: in some cases, it may simply be a title/term, in others, it might be a question. For now, let’s assume both are workable. However, in both cases, why not shift our understanding away from thinking about vocabulary as word lists that pupils should encounter along the way, towards vocabulary as representing concepts that underpin bigger, more powerful ideas that will support a much more profound understanding of the content? In other words, vocabulary isn’t an optional add-on or a nuisance: as a teacher, ask not what you can do for literacy, but ask what literacy can do for you! This needn’t be about rewriting curricula: it’s about clarifying our own conceptual reference points so that we can make it simpler for our pupils. Put simply: vocab helps us join the dots!

Let’s look at an example, thinking about how we could introduce A Christmas Carol:

As experts, we may have confidence that both columns represent the same thing. But we’re human: there’s no guarantee that we will remember to explicitly teach these ideas to pupils in the course of those lessons. Rather, as leaders and teachers, why not tweak our curricula to explicitly outline these ideas and make it visible for everyone?

As Ludwig Wittgenstein so memorably said: “the limits of my language are the limits of my world.” So let’s expand our pupils’ worlds. Let’s give them access to thinking and writing just like us: the experts.