Scaffolding: what it is and what it isn’t

At first glance, it can be easy to confuse well-placed scaffolding with simply telling learners how to complete a task - something many teachers and educational leaders shy away from. We want to give learners the skills and the independence they need to complete tasks unaided.

In actual fact, scaffolding is an effective way of doing this. Rather than handing learners the answers, scaffolding involves putting procedures and structures in place that guide learners through tasks, making new knowledge accessible and boosting their independence through practice.

Scaffolding is a method of instruction that unlocks new tasks for learners, guides them through the task with increasing confidence, and slowly removes itself when learners are able to complete the task independently. For example, a learner who is encountering a new skill for the first time might need plenty of scaffolding from the teacher to understand the task, whereas a learner with previous experience might need much less, or none at all.

Eventually, the end goal of scaffolding is to render the scaffolding unnecessary - through the benefits of scaffolding, learners are now able to complete tasks and utilise new knowledge without help or guidance, and have the confidence to do this across all subjects, inside and outside of the classroom.

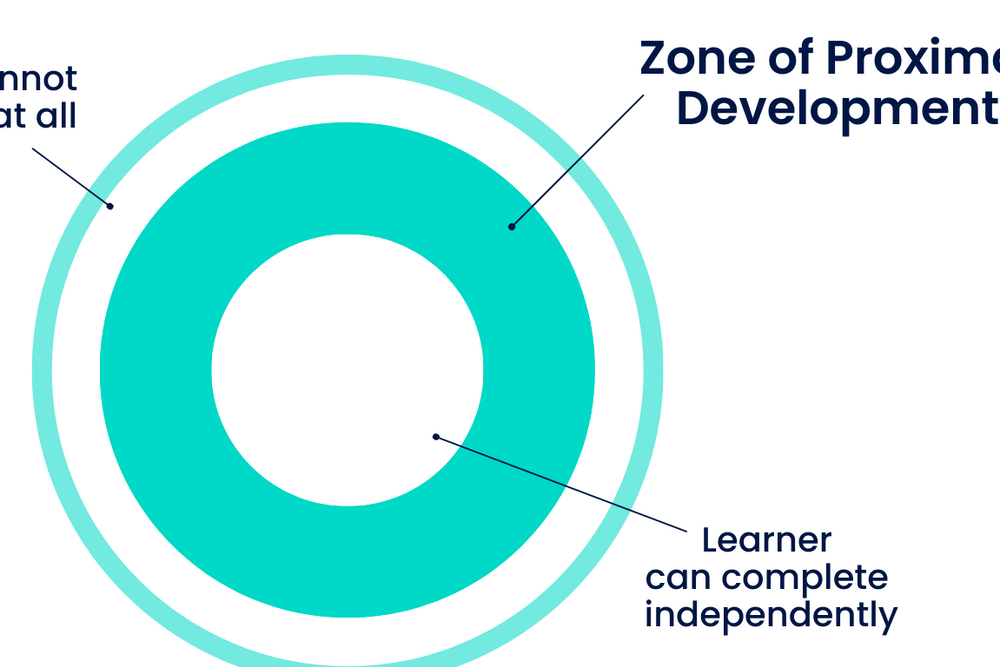

To scaffold effectively, teachers have to figure out the perfect gap between what learners can do on their own, and what learners need additional support to complete. This provides learners with the opportunity to practise skills they already have, while allowing them access to new information.

The development of the scaffolding theory

Vygotsky

The origin of the scaffolding theory comes from Vygotsky’s theory of proximal development - locating a space between what learners can complete aided and what they can complete unaided. This proximal gap is the zone where learners can complete a task with help, and this is where scaffolding is effective for development.

Vygotsky’s theory of proximal development involves taking a learner closer to their full potential through small, manageable tasks, chunked up and scaffolded. For example, a typical twelve-year-old learner would not be able to do complicated quadratic equations on their own, but the introduction of basic algebraic sums, supported by the teacher, would bring them a step closer to that full potential.

Looking at it this way, a twelve-year-old encountering simple algebraic sums for the first time, with a previous knowledge of how to add and subtract numbers up to four digits, would be in their zone of proximal development. With scaffolding, they are in the right place to learn new knowledge that will bring them closer to their potential - the complicated algebraic equations they might encounter in their GCSE or A level years of mathematics.

Much like a child learning to walk and talk, learners progress faster when they are guided by adults who know more than they do: teachers. Vygotsky identified this, and acknowledged that learners achieve their potential faster with the support and guidance of teachers.

Rosenshine and scaffolding

Rosenshine built on Vygotsky’s early theories of scaffolding with his 10 principles of instruction. These principles highlight steps teachers can take to ensure their teaching is scaffolded effectively, helping learners achieve their true potential.

1. Begin the lesson by reviewing the previous lesson

Reviewing helps us to transfer information into our long-term memories. With vital information retained, learners are one step closer to mastering tasks that require that information. Research by Rosenshine found that eight minutes of review at the start of the lesson led to higher achievement scores than those earned by learners in other classrooms, and this applied to both mathematics and vocabulary acquisition.

2. Present new material in small steps with practice after each

In 1956, George Miller presented the theory that people can only hold seven items in their working memory at any one time, plus or minus two items. This was one of the first times human memory was discussed as having finite “slots” for information to go into, so not all new information would be retained. This theory informs Rosenshine’s second principle of instruction - breaking new material into small steps, allowing the mind to transfer information to the long-term memory.

3. Help learners practise new information by asking plenty of questions

Every question you give your learners as a teacher provides them with an opportunity to utilise the new information they have learned. Through this, new material is consolidated and moved one step closer to mastery. Rosenshine’s studies found that in less effective teacher classrooms, teachers asked an average of nine questions to their learners in any one lesson - in contrast with this, more effective classrooms spent the vast majority of the lesson demonstrating new information and following it up with examples, questions and practice activities.

4. Use models to guide learners

When encountering a new task for the first time, learners often need cognitive support to complete the task. Even when learners have all of the necessary information to complete a task successfully, if the structure and cognitive requirement of the activity is new, it will need additional modelling.

One way of providing this support is through thinking aloud. A teacher walking the class through their thought process when approaching a task such as the one set provides a model for the learners to work off of. Another way of doing this is through models and worked examples - this could be a model essay, where the teacher has highlighted the steps they have taken to meet the exam criteria, or an extended maths problem where the teacher has shown their working.

5. Guide student practice

When information is presented through modelling and questioning, it’s simpler for learners to understand - but this doesn’t necessarily mean they will remember it. Embedding new knowledge into learners’ long-term memory takes practice, facilitated by the teacher. Learners retain information best when given the opportunity to rephrase it, apply it to existing knowledge, and experiment.

Questioning, as mentioned above, is one part of the memorisation process, but it’s important to dedicate time in class to practising new skills. While this takes more time in lessons, it reduces the amount of reteaching necessary in the future - and giving learners feedback on their practice boosts their confidence, whilst ensuring the information they memorise is correct.

6. Check for student understanding

As shown in practice activities, it is important that learners memorise and master the correct information and skills. This means regularly checking with your class for misconceptions and weaknesses in their learning. Asking questions is a great way to do this; in some classrooms, teachers may put the onus of asking questions onto the class, which is something less confident learners might not do - if they are not confident on what they know, how can they be confident on what they don’t know? By shouldering the responsibility of asking questions themselves, teachers can identify misconceptions easily.

Another method of doing this is through asking learners to show their planning. This could be an essay scaffold in English, or showing their working in Maths. When learners present their thought process on the page, you can identify where they might have gone wrong and reinform them.

7. Obtain a high success rate

Research shows that the optimal success rate for boosting learners’ attainment is 80%. This means 80% of answers given orally or in practice activities are correct - and this is from all students, not just the most confident. A high success rate ensures that learners don’t practise misconceptions in their own time, and do not arrive to the next lesson without the groundwork of the previous lesson’s knowledge. All students have the potential to succeed when presented with new information - it is just a matter of providing the right amount of scaffolding to get them there.

8. Scaffold difficult tasks

The tasks that learners find difficult may vary from student to student - this means that scaffolding has to be flexible. Scaffolding for the whole class includes methods shown above, such as thinking aloud and modelling, but individual scaffolds can include checklists and prompt cards.

As well as this, scaffolding allows teachers to predict future difficulties that learners may face. When a task increases in complexity, or requires multiple learned skills to be combined, learners already have a scaffold they are used to - even if they were able to complete the initial task independently, they can fall back on that original scaffold to tackle more difficult activities, boosting learning long term.

9. Monitor independent practice

After guided practice, comes independent practice. Learners work on their own, continuing their practice of new skills. Independent practice links to the theory of “overlearning” - learners who become automatic with new skills are able to dedicate more cognitive energy to applying the skill rather than recalling how to use it.

To achieve this, learners must practise new skills in their own time so that they can master the skill and use it automatically. To support learners in their independent practice, set activities that require the same skills as the guided practice, as learners have already been supported in completing these tasks and have had adequate scaffolding. This allows them to access the independent practice activities, developing their confidence using these skills and readying them to build on them in the next lesson.

10. Review skills regularly

To make sure new skills are firmly within learners’ long-term memories, return to the skill on a weekly or monthly basis and review it. The length of time between reviews can vary depending on learners’ confidence with the skill - again, aiming for that 80% success rate in every lesson. Returning to previously learned skills can help learners connect new information with prior knowledge, allowing them to apply mastered knowledge to new situations. When content is reviewed frequently, the links between previously learned information strengthens. The more information is within learners’ long-term memories, the less space it requires in their working memory, leaving room for new skills.

Why should we use scaffolding?

As shown in Rosenshine and Vygotsky’s research, scaffolding allows students to learn new skills in the optimal way. Scaffolding identifies the gap between knowledge learners have mastered and knowledge they do not understand. This gap, the zone of proximal development, is the information learners can master through effective scaffolding. Targeting this zone with the right scaffolding allows learners to acquire new skills faster than they would independently, and helps learners move information into their long-term memories. This allows them to apply the skills they have learned when it comes to learning new information, or sitting down for their exams.

The effectiveness of scaffolding

Rosenshine’s research shows that classrooms with higher success rates use more methods of scaffolding than less successful classrooms. Teachers who used techniques such as thinking aloud, model answers and guided practice spent less time reteaching content further down the line, and learners had better understanding overall.

For example, Rosenshine’s research showed that more successful Maths teachers spent 23 minutes in a 40-minute period in active teaching - demonstrating new skills, asking questions, modelling responses and facilitating guided practice - while less effective teachers only taught new information for 11 minutes, only asking 9 questions throughout the whole lesson. The teacher whose lesson took the time to scaffold students’ learning spent less time in the future clearing up misconceptions in independent practice, as learners have a deeper understanding first time around.

Whether it’s used in Maths, Science or English, scaffolding has a positive effect on learners’ attainment - and, done right, these techniques can prevent confusion and save teachers time in the long run.

Implementing scaffolding

Throughout his 10 principles of instruction, Rosenshine lays out a potential lesson plan for a teacher wishing to incorporate scaffolding into their lessons. Beginning the lesson with a quick recap activity, such as a Question of the Day or a Think Pair Share, is a great way to begin implementing scaffolding into your classroom.

As well as this, incorporating model answers into your lesson plan is a simple way to implement scaffolding: complete a practice question yourself, then present your work to the class and talk through your thought process when completing the piece. For additional support, provide a checklist with the criteria for completing the task - this is very effective when writing essays, such as in History or Psychology.

Just by incorporating those simple steps, your time spent actively teaching and scaffolding will increase, boosting learners success rates. From there, Rosenshine’s subsequent principles can be incorporated, such as guided practice and independent learning.

Scaffolding in early years: the role of play

We have probably all used scaffolding techniques at some point in our lives, but perhaps we didn’t realise it. Playing with early years children is a great example of scaffolding in practice - when we play with young children, we automatically use many of the principles highlighted by Rosenshine.

For example, when showing a three-year-old how to play with blocks, we might create our own tower to demonstrate the capabilities of the building blocks. When we do this, we encourage the child to think: “What else can these blocks do?” This is an example of modelling - we have modelled a skill for them that, when mastered, will open up future possibilities for the blocks.

As well as this, we often talk children through a task when they are completing it, such as when a child is building with blocks. “Do you think this one could go here?” “What do you think might happen if we put that block there?” When we do this, we are vocalising our thought process, encouraging them to think about the effects of their actions. These skills that come naturally to us in early years play are the same skills that are effective in classroom teaching (though perhaps altered slightly for your teenage learners…)

Examples of scaffolded learning

Daily review activities

- Daily quiz question

- Think-pair-share

- Flashcard activities

- Taboo - learners describe a concept without using certain words

Scaffolding new skills

- Thinking out loud

- Modelling responses

- Checkbox mark schemes

- Visual models for planning, such as for essays

- Group planning

- Small groups of the whole class work together to complete a task following the model

Guided practice

- "Put your hand up if you know the answer."

- Practice questions

- Learners level up each other's responses

- Create your own model/plan

- Frayer models

Independent practice

- Homework activities

- Workbooks

- Edtech solutions such as Bedrock's core curriculum and Bedrock Mapper.

- Presentations

- Supervised seatwork

- Knowledge organisers

Making scaffolding work in the classroom

To make the implementation of scaffolding in the classroom easier, Rosenshine went into more depth with his principles. These 17 principles, up from 10, provide a concrete plan on what to include in your lesson plans for scaffolding to work effectively. When done in unison, these 17 principles work together to boost learners’ attainment and prepare them for success.

Rosenshine found that teachers who spent more time scaffolding, and guiding practice activities went on to spend less time supporting learners through independent practice; learners already understood the skills needed and were confident enough to do the tasks independently. While implementing scaffolding techniques might seem overwhelming at first glance, they are selected in an order that saves teachers time while improving outcomes for learners.

To make Rosenshine's principles even more accessible to the classroom teacher, Tom Sherrington compiled the most important principles into 4 main strands that can be implemented easily.

How Bedrock uses scaffolding to teach difficult concepts

Bedrock incorporates scaffolding into our deep-learning algorithm, ensuring every learner makes progress.

In Bedrock’s vocabulary curriculum, learners are guided through a bespoke text and provided explicit vocabulary definitions, further scaffolded by contextual examples. The lessons then go on to guide learners through practice activities, before facilitating an independent practice task at the end. After completing a lesson, learners are given recap activities at regular intervals to ensure new vocabulary is transferred to their long-term memories.

This is similar to Bedrock’s grammar curriculum with the addition of recap lessons. With Bedrock’s grammar recap lessons, learners can access prior knowledge at any time, helping to scaffold future learning. As well as this, learners are guided through tasks that allow them to use, question and experiment, with new grammar skills, helping them to master these skills.

While Bedrock alone isn’t enough to replace the effects of a brilliant classroom teacher, EdTech solutions like Bedrock Learning can support the effective implementation of scaffolding into your lesson plans.